Helicobacter pylori is commonly framed as a simple infection that requires eradication. Treatment regimens are debated, resistance rates are tracked, and success is measured by post treatment testing.

Yet in routine clinical practice, many failures attributed to therapy have little to do with antibiotics. They begin much earlier; at the level of diagnosis, interpretation, and context.

The Comfort of a Binary Answer

Modern clinical workflows tend to favour clarity where a test is either positive or negative, treatment is given or withheld or Cure is either confirmed or questioned.

H. pylori fits neatly into this model. If detected, it is treated and if not detected, the stomach is often assumed to be free of its influence. This binary framing is convenient, but it oversimplifies a far more complex biological reality. The stomach is not uniform. Bacterial density varies by region. Acid suppression alters colonisation patterns. Inflammation is patchy.

Most importantly, colonisation fluctuates over time rather than remaining static. Diagnosis, unfortunately, is often a snapshot of a “dynamic target”.

Where Diagnostic Assumptions Break Down

Many commonly used tests rely on assumptions that we rarely stop to examine.

For example in the case of biopsies we assume a single tissue sample represents the entire surface area of the stomach.

While in the Rapid Urease Test we assume it will turn positive even when bacterial density is low or patchily distributed.

As for non-invasive tests like the Urea breath testing, it is sensitive but not always accessible. Stool antigen testing depends heavily on sample handling and timing.

The fact of the matter is each test captures a moment but none captures the system.

When diagnostic certainty is overestimated, treatment decisions arguably rest on fragile foundations. A negative result is often taken as reassurance rather than what it actually is…… a partial information.

The Indian Paradox and the Trap of Blanket Eradication

This issue is particularly acute in India. We face a unique challenge where the prevalence of H. pylori is high, yet gastric cancer rates in many regions are lower than expected. At the same time, dyspeptic symptoms, anaemia, and functional disorders are widespread.

In this context, blanket eradication strategies raise uncomfortable questions.

Treating every detected infection does not always translate into clinical benefit. In fact, it may expose patients to repeated antibiotic courses and disrupt the gut microbiota without addressing the underlying physiological driver of their symptoms.

The decision to eradicate should be anchored in more than just detection. It requires looking at the disease stage, symptom pattern, risk profile, and the functional status of the stomach.

Diagnosis must inform judgement, not replace it.

Infection as a System Disruptor

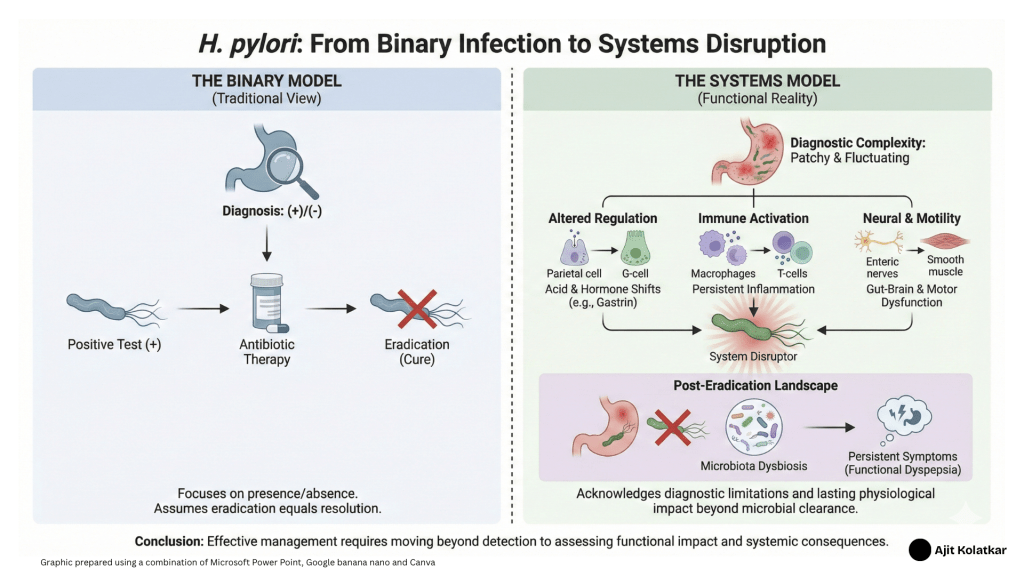

We often forget that H. pylori does not act merely by occupying space on the mucosa. It is a system disruptor.

It alters acid secretion and modifies gastrin 17 signaling. It shifts immune responses and modifies local neural responses.

These changes can persist even when bacterial load decreases or becomes hard to detect. Symptoms may continue, function may remain impaired while the stomach enters a chronic low inflammatory state.

This explains why some patients feel unchanged after documented eradication, while others improve despite incomplete therapy. The system response matters as much as the bacterial presence. A negative test in a symptomatic patient does not prove a “normal” stomach. It often just reflects the limitations of our tools.

This figure contrasts the traditional linear approach to Helicobacter pylori management with a systems-biology perspective that accounts for physiological and ecological complexity.

The Hidden Cost of Eradication

Eradication therapy is not a neutral intervention. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and potent acid suppression alter not only H. pylori but the wider ecosystem of the gut. These changes can influence stomach function, bile acid metabolism, motility, mucosal immunology and immune signaling long after the therapy is finished.

In some patients, eradication is followed by new or persistent symptoms. Post treatment dyspepsia and altered bowel habits are not uncommon. These are rarely framed as treatment consequences…… they should be.

Understanding eradication as a system level intervention forces us to consider the downstream effects, not just the immediate goal of microbial clearance.

Antibiotic Resistance is a Conceptual Failure

We often cite rising antibiotic resistance as the primary obstacle to success. Resistance matters, but it is also a “symptom” of how we approach the problem.

Repeated empirical therapies, poor initial diagnosis, and a “failure to stratify risk” all contribute to unnecessary antibiotic exposure. When eradication is attempted without clarity of indication, resistance becomes inevitable.

In this sense, resistance is not merely a microbial problem. It is a conceptual one.

Rethinking the Diagnostic Question

Perhaps the meaningful question is not simply “Is H. pylori present?”

The better questions should be functional or physiologically driven!

How is the stomach regulating acid in this patient?

How is the immune system responding?

Is the symptom profile actually driven by the infection, or is the infection an incidental bystander to a motility disorder?

Answering these questions requires moving beyond single tests and binary outcomes. It requires pattern recognition.

Looking Ahead

Future posts will explore these themes in greater depth. We will look at the role of gastric function testing, the interpretation of biomarkers beyond standard cutoffs, and the interactions between infection and motility.

H. pylori is a useful starting point because it exposes a recurring flaw in how we frame disease. Host response matters and needs to be taken into account.

Before it becomes a treatment problem, it is a diagnostic one.

Before it becomes a structural disease, it is functional disruption.

Understanding that distinction matters if we want to intervene earlier, treat more thoughtfully, and do less unintended harm.

Leave a comment